Understanding the effects of aquatic exercise on human health and physiology

By Dr. Bruce E. Becker

A considerable amount of research has been accumulated over the past 50 years on the effects of aquatic immersion on the human body, much of which began during the period NASA was planning to put an astronaut into space using aquatic immersion as a proxy for weightlessness.

These effects were profound and spurred further research on the cardiovascular, pulmonary and renal effects of aquatic immersion. This research, however, was not focused on the effects of aquatic exercise. To this day, there are several important questions that remain either underexplored or unexplored about the place of aquatic exercise in the management of important health issues such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, obesity, respiratory disease and chronic neurologic diseases such as multiple sclerosis, Parkinsonism, and the late effects of polio.

This is a tragic lack of research for the industry, as the research that has been completed demonstrates a great potential for human health benefit across a wide range of diseases that cause untold economic cost upon societies across the globe.

Swimming for heart health

Non-communicable diseases cause 60 per cent of all deaths worldwide and nearly half of these are from cardiovascular disease. In fact, cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death in the U.S. (one in every three deaths is from heart disease and stroke, equal to 2,200 deaths per day), and the second in Canada (every seven minutes someone dies from heart disease or stroke). The larger issue at hand, however, is these conditions are also the leading causes of disability, preventing people from working and enjoying family activities. Cardiovascular disease is also incredibly expensive—both heart disease and stroke hospitalizations in the U.S. cost more than $444 billion in health care expenses and lost productivity, while it costs the Canadian economy more than $20.9 billion every year.

The factors that lead to cardiovascular disease are well publicized: smoking, hypertension, lack of physical fitness, diet, obesity, blood lipids, carbohydrate metabolism and insulin sensitivity. Exercise is touted as a major health-promoting activity to reduce the potential risks of developing cardiovascular disease; swimming is often included within these recommendations, however, there has only been a small body of research assessing the impact of aquatic exercise and swimming upon cardiovascular risk factors.

Studies show swimming can help lower blood pressure

Swimming has been shown in several studies to lower blood pressure significantly, especially in hypertensive individuals. Interestingly, some research has demonstrated a slight rise in blood pressure in normotensive individuals, but these blood pressure elevations did not exceed current standards for hypertension. Overall, the literature certainly supports the belief that a program of regular aquatic exercise (swimming) produces a beneficial effect upon blood pressure regulation, especially in hypertensive individuals.

In the late ’80s, research started to emerge demonstrating the cardiovascular system was capable of responding positively to a program of swim training in previously sedentary middle-aged individuals. The responses included an increase in the ability of the arteries to dilate during exercise, whereas in sedentary individuals this ability is greatly reduced as the arterial system loses its elasticity without exercise. This loss in elasticity is a precursor to hypertension, which further raises the risk of cardiovascular disease.

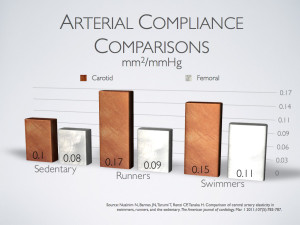

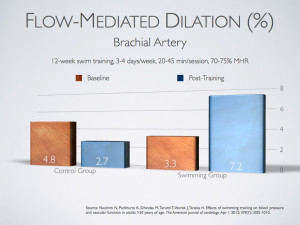

More recent research has both supported and expanded these findings. For example, a study published earlier this year in the American Journal of Cardiology, showed a 12-week swimming exercise program comprising a group of previously sedentary individuals produced more than a 20 per cent increase in arterial compliance, a measure of arterial elasticity, and also a significant decrease in blood pressure compared to their control group (see Figures 1 and 2). An earlier study by this group of researchers compared regular middle-aged and older runners and swimmers with sedentary controls and showed that swimmers and runners both showed major positive differences from sedentary controls in arterial compliance. These are important findings, as the ability of the vascular tree to quickly respond to the increased demands of exercise are extremely important in reducing the work of the heart in circulating blood throughout the body and reducing the risks of hypertension and cardiovascular disease.