Building swimming pools

by Sally Bouorm | February 1, 2013 2:13 pm

[1]

[1]By John Petrocelli

Concrete is undoubtedly one of the most widely used materials in construction. It is used in everything from sidewalks and skyscrapers to swimming pools and landscapes. Much of this is due to its relative abundance, ease of use, portability, and cost effectiveness. Due to its physical properties, concrete is best suited for applications where it is loaded axially in compression (i.e. columns, slabs on grade, etc.). Concrete has an extremely high compressive strength with a normal range of 15 to 32 MPa (2,175 to 4,641 psi) in the pool and landscaping industries. This is perhaps the most popular and well-known property of concrete and is often the only one used to specify a concrete mix in pool and landscape projects.

[2]

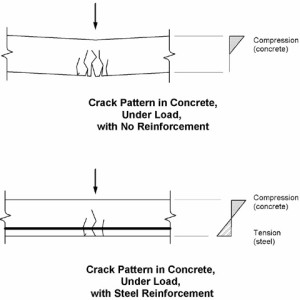

[2]Unfortunately, this heavily utilized building material has its limitations. While concrete is strong in compression (pushing forces), it is extremely weak in tension. Therefore, it will crack easily if exposed to ‘pulling forces.’ In most structures, tension forces are present; therefore, plain concrete is not a suitable building material. However, by incorporating steel into the concrete, a hybrid building material is created, which offers strength in both compression and tension (see Figure 1).

When structural steel, in the form of reinforcing rods (rebar) is added to the plain concrete, the resulting hybrid material is called reinforced concrete (RC). The rebar is positioned where the structural member will experience tensile stresses, and in doing so, will provide the tensile strength needed. Engineers use structural analysis to calculate the magnitude and location(s) of stresses within each member of a reinforced concrete structure.

History of steel

The development of steel traces back 4,000 years to the beginning of the Iron Age. Before iron (Fe), bronze was used for everything from construction, architecture, jewellery, and weaponry. Its major flaws, however, was that it was relatively weak and hard to find.

Eventually, bronze was replaced by iron simply because it was harder and stronger. By the 17th century, the properties of iron were well understood and it became the most abundant material used in civilization. As more and more uses were found for iron, its popularity as a building material continued to grow.

By the 19th century, its use peaked due to the incorporation of steel to build the railway systems; however, it was far from being a perfect material as it was still fairly brittle and expensive to make. As a result, governments created monetary incentives to improve the properties and processes of steel. Metallurgists (someone who examines the physical and chemical behaviour of metals and alloys) were highly rewarded for developing ways to make metal less brittle and cheaper to produce. As a result of these incentives, in 1856 Henry Bessemer[3] developed an efficient way to use oxygen (O) to reduce the carbon (C) content (responsible for the brittleness) of iron, and hence, creating the modern day steel. With its more ductile properties and its less expensive processing, steel eventually found many more uses.

Modern day steel

Today, there are many different types of steel, e.g. alloy, stainless steel, tool steel, and the most common, carbon steel. The latter is widely used in construction as structural steel and to create reinforcing steel or rebar. The main alloying constituent of this steel is carbon.

The American Iron and Steel Institute (AISI) defines carbon steel as the following: “Steel is considered to be carbon steel when no minimum content is specified or required for chromium (Cr), cobalt (Co), molybdenum (Mo), nickel (Ni), niobium (Nb), titanium (Ti), tungsten (wolfram [W]), vanadium (V), or zirconium (Zr), or any other element to be added to obtain a desired alloying effect; when the specified minimum for copper (Cu) does not exceed 1.04 per cent; or when the maximum content specified for any of the following elements does not exceed 1.65 per cent manganese, 0.60 per cent silicon, and 0.60 per cent copper.”

Carbon steel is classified as either:

- Mild/low (structural steel)

- Medium (automotive parts)

- High (springs and high-tensile wires)

- Ultra-high (knives/cutlery, axels, etc.)

Steel grades and types

There are approximately 3,500 different grades of steel. They are composed of iron and carbon and other impurities and alloying elements. It is the variation of these impurities and alloying elements that result in all the different varieties of steel grades. The carbon content also varies to form different grades of steel. It typically ranges from 0.1 to 1.5 per cent, with the most widely used range being 0.1 to 0.25 per cent. The properties required or the application will dictate the composition of each variety of steel, each having its own benefits.

Carbon steel properties

The following are some of the most popular physical properties of steel that result in its use as a reinforcing material for reinforced concrete:

- Density 7,850 kg/m3 (490 lb/cf)

- Elastic modulus 190 to 210 GPa (27,500,000 to 30,000,000 psi)

- Poisson’s ratio[4] 0.27 to 0.3

- Thermal expansion 11 – 16.6 (10-6 /K)

- Tensile strength 276 to 1,882 MPa (40,030 to 272,961 psi)

- Yield strength 186 to 758 MPa (26,977 to 109,938 psi)

- Per cent elongation 10 to 32 per cent

- Hardness 86 to 388 HB (Brinell 3,000 kg)

Of the above physical properties, the most significant in terms of the creation of reinforced concrete are the coefficient of thermal expansion and the tensile strength in comparison to concrete. The upper limit of the coefficient of thermal expansion of plain Portland cement concrete is approximately 13 (10-6 /C), which is similar to that of steel, eliminating large internal stresses due to differences in thermal expansion or contraction.

This is important since the effects of temperature will not create additional ‘internal’ forces that need to be accommodated in addition to the physical loading conditions of the reinforced concrete member. As mentioned above, reinforcing steel is placed into concrete in the areas where tensile stresses will be present as a result of design loading. As the tensile strength (resistance to tensile loads) of steel is between 30 to 50 times greater than that of concrete, it is ideally suited as reinforcement in tension areas of the structural member. Both of these properties help reinforcing steel work in unison with concrete to create a super building material that is strong in both compression (concrete) and tension (steel).

Applications of steel

Steel is the most widely used and recycled metal material on earth due to its high strength and relatively low production cost. The five main sectors in which steel is used are:

- Appliances and industry

- Packaging

- Energy

- Transportation

- Construction

By far, the majority of steel is used in the construction industry due to the fact that structures can be built relatively quickly and inexpensively in comparison to other materials. Structural steel is used in the following construction applications:

- Low- and high-rise buildings;

- Schools and hospitals;

- Bridge deck plates;

- Piers and suspension cables;

- Harbours;

- Cladding and roofing;

- Offices;

- Tunnels;

- Security fencing;

- Coastal and flood defences;

- Reinforced concrete (rebar); and

- Swimming pools.

Reinforcing bar (rebar)

Reinforcing steel (rebar) is made from carbon steel and is the primary type of structural steel used in creating reinforced concrete structural members. Rebar is normally round in cross-section and is ridged (deformed) along its length. These ridges are responsible for transferring loads (stresses) from the concrete to the steel via mechanical bond.

It is normally placed into plastic concrete (the stage at which fresh concrete can be moulded), or plastic concrete is poured around the rebar cage. The concrete flows around and completely covers the rebar. Once hardened, the rebar and concrete essentially move and respond to loading conditions as one. Hence, reinforced concrete is formed.

The concrete primarily provides mass and resistance to crushing loads, while the rebar provides strength in tension and flexure. The concrete also serves to protect the rebar from corrosion by forming a passive layer of protection over the steel as they chemically interact when the plastic concrete is placed onto the rebar.

The alkaline (AT) environment of the fresh concrete paste makes the steel much more resistant to corrosion than it would be in a more neutral or acidic pH environment. As long as the steel is fully coated by concrete, it is less likely to corrode. However, many structural members get loaded beyond their design strength and as a result develop tension cracks, which allow atmospheric elements to reach the embedded rebar, which initiates the corrosion process.

This is one mode of failure of structural members and structures; once corrosion starts, it will continue to spread and eventually accelerate the complete failure of the structure, unless it is rehabilitated in time.

Rebar sizes and grades

Once the architect or designer comes up with the structure’s overall ‘look,’ engineers use structural analysis and building codes to determine the loads the structure will be subjected to and the internal stresses that will result from this loading and configuration.

Each member of a reinforced structure must be designed based on the following primary parameters: concrete cross-section size (i.e. length and width) of the member, and the location and amount of reinforcing steel.

The size and number of bars specified will be dictated by the size of the load (stresses) to be resisted and the size of the member (cross-section). The primary calculation is to determine the total cross-sectional area of steel required to safely resist the design loading. An engineer will specify the location, size, and number of bars required in the cross-section.

Rebar is specified in both metric (Canadian) and imperial (U.S.) sizes. In Canada, most builders still tend to refer to rebar by the imperial sizes; however, rebar is typically sold in Canada by the metric bar designation. Therefore, it is extremely useful to understand the relationship between both.

In U.S. sizes, imperial bar designations represent the bar diameter in fractions of ⅛ in., such that #8 (8⁄8 in.) represents a 1 in. diameter (see Figure 2).

U.S. Imperial Bar Designations |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Bar size | Weight per unit length (lb/ft) | Nominal diameter (in.) | Nominal area (mm2) |

| #3 | 0.376 | 0.375 (3/8) | 71 |

| #4 | 0.668 | 0.500 (1/2) | 129 |

| #5 | 1.043 | 0.625 (5/8) | 200 |

| #6 | 1.502 | 0.750 (3/4) | 284 |

| #7 | 2.044 | 0.875 (7/8) | 387 |

| #8 | 2.67 | 1 | 509 |

| #9 | 3.4 | 1.128 | 645 |

| #10 | 4.303 | 1.27 | 819 |

| #11 | 5.313 | 1.41 | 1006 |

| #14 | 7.65 | 1.693 | 1452 |

| #18 | 13.6 | 2.257 | 2581 |

| #18J | 14.6 | 2.337 | 2678 |

In Canadian sizes, metric bar designations represent the nominal bar diameter in millimetres rounded to the nearest 5 mm (see Figure 3). For example, a 10M bar actually has a nominal diameter of 11.3 mm, but is rounded down to 10 mm.

Canadian Metric Bar Designations |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Bar size | Mass per unit length (kg/m) | Nominal diameter (mm) | Cross-sectional area (mm2) |

| 10M | 0.785 | 11.3 | 100 |

| 15M | 1.57 | 16 | 200 |

| 20M | 2.355 | 19.5 | 300 |

| 25M | 3.925 | 25.2 | 500 |

| 30M | 5.495 | 29.9 | 700 |

| 35M | 7.85 | 35.7 | 1000 |

| 45M | 11.775 | 43.7 | 1500 |

| 55M | 19.625 | 56.4 | 2500 |

By comparing the nominal cross-sectional areas of the above charts, correlations can be derived between metric and imperial bar sizes as follows:

- #3 < 10M < #4;

- 15M = #5;

- #6 < 20M < #7;

- 25M = #8;

- #9 < 30M < #10;

- 35M = #11;

- 45M = #14; and

- #14 < 55M < #18

Principles and methods for reinforced concrete

Reinforced concrete can be used for many types of structures and components, including foundations, walls, columns, slabs, beams, and more. Concrete swimming pools contain several of these structural members.

Concrete footing

[5]

[5]First, structural concrete pools are usually built upon a reinforced concrete footing. The footing is designed to support the weight of the pool walls, properly bridge the soil foundation below, and resist applied loadings on the walls. The footing design is heavily dependent on the soil and loading conditions and should be calculated by a professional engineer.

A common rule of thumb for simple concentric/axial loading and firm/undisturbed soil is the footing width should be at least two times the thickness of the wall it is supporting, while the footing’s thickness should be comparable to the wall it is supporting. It is common to install two rows of rebar that is at least 10M or 15M.

Pool walls

[6]

[6]| General Steps in Designing a Singly Enforced Concrete Beam (or Wall) |

|---|

| 1. Perform structural analysis on the beam to determine the internal stresses (due to the loading factors). 2. Specify the compression strength of the beam. 3. Specify the tensile strength of the steel reinforcement. 4. Determine the cross-sectional dimensions of the beam. 5. Calculate the area of steel required (to resist the internal stresses). 6. Select the area of steel provided (combination of rebar sizes from the charts). 7. Calculate the area of the compression block (section of beam in compression). 8. Specify the positioning of the steel in the cross-section and specify the minimum concrete cover 40 to 50 mm (1.5 to 2 in.) to prevent spalling, etc. 9. Calculate the nominal moment strength of the beam (resistance to bending stresses). 10. Compare to the moments (bending stresses) determined by structural analysis (Step 1) and ensure moment strength (Step 8) is larger. 11. Sketch the beam for fabrication. |

The pool walls themselves are reinforced concrete walls. Normally, they are 1.2 to 1.5 m (4 to 5 ft) in height and 203 mm (8 in.) thick. A common reinforcement arrangement is a 10M or 15M bar at 200 to 300 mm (8 to 12 in.) in both horizontal and vertical directions (grid). Unless a builder has a lot of experience with forming and pouring reinforced concrete walls, they must consult a licensed professional engineer to determine the thickness of both the pool walls and the amount and location of reinforcing steel.

Pool floor

[7]

[7]The pool floor is similar to a slab on grade in design and construction. Slabs on grade are likely the simplest structural members to design/build. In most cases, builders will continue the wall reinforcing pattern through the pool floor. This is more than adequate, especially if the pool floor is built on firm, undisturbed soil. For disturbed soil conditions, or soft ground, an engineer must be consulted as thicker concrete and additional reinforcing steel will likely be required to bridge the non-ideal soil conditions.

The principles and methods for reinforced concrete are being constantly revised as a result of theoretical and experimental result:

- Working stress method with a focus on conditions of service load.

- Strength design method with a focus on conditions at loads greater than service loads when failure may happen. The former method is now considered obsolete.

Analysis and design

Before an engineer can design a reinforced concrete member, they must know the forces that will be present in the structure/member. This is a function of the structure’s overall design, how the members are connected (i.e. ridged joints, pins, etc.), and the loading for which it is being designed.

[8]

[8]Assuming the overall appearance and connection details are known, the forces are determined by using static equilibrium, applied mechanics, and free body diagrams to determine the internal forces. Static equilibrium implies that for a structure to be stable (at rest), the sum of all forces acting on it (actions and reactions) must be zero. Applied mechanics is considered the backbone of all structural engineering. It deals with the basic concepts of force, moment (force x distance), and its effects on the bodies. It helps to understand how different bodies behave under the application of different types of loads. Applied mechanics provides the basis for structural analysis, which is required for structural design.

By combining two different materials (concrete and steel) with certain similar and different properties, a hybrid material is produced, which is strong both in tension and compression. Due to its relative affordability, ease of use, and abundance, reinforced concrete is a highly versatile building material used in structural concrete swimming pools, retaining walls, slabs, and foundations.

Editor’s note: This is the follow up article to Petrocelli’s feature on understanding the properties and characteristics of concrete, which appeared in the December 2012 issue of Pool & Spa Marketing.

John Petrocelli, P.Eng., is the president of Spider Tie Canada Inc., a Canadian distributor of Spider Tie products. He holds a degree in civil engineering from the University of Toronto, specializing in concrete construction, structural engineering, soil mechanics, and project management. Petrocelli is also a licensed professional engineer in Ontario and a member of the Professional Engineers Ontario (PEO) and the Ontario Society of Professional Engineers (OSPE). He can be reached via e-mail at jpetrocelli@spidertie.ca[9] or by calling (416) 655-8171.

John Petrocelli, P.Eng., is the president of Spider Tie Canada Inc., a Canadian distributor of Spider Tie products. He holds a degree in civil engineering from the University of Toronto, specializing in concrete construction, structural engineering, soil mechanics, and project management. Petrocelli is also a licensed professional engineer in Ontario and a member of the Professional Engineers Ontario (PEO) and the Ontario Society of Professional Engineers (OSPE). He can be reached via e-mail at jpetrocelli@spidertie.ca[9] or by calling (416) 655-8171.

- [Image]: http://poolspamarketing.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/bigstock-Rebar-grid20923E6.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.poolspas.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/tension-rebar-reduces-tension-cracking.jpg

- Henry Bessemer: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/

- Poisson’s ratio: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Poisson%27s_ratio

- [Image]: http://www.poolspas.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/reinforced-concrete-pool-footing.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.poolspas.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/reinforcing-steel-for-pool-wall.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.poolspas.ca/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/pouring-reinforced-concrete-pool-wall.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.poolspas.ca/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/completed-reinforced-concrete-pool-structure.jpg

- jpetrocelli@spidertie.ca: mailto:jpetrocelli@spidertie.ca

Source URL: https://www.poolspamarketing.com/trade/building-swimming-pools/