Common facility operational issues are often blamed on the dehumidifier

By Ralph Kittler

Canada has thousands of indoor swimming pools. Unfortunately, many of them are more problematic than facility operators would like to admit. Too often, the pool’s dehumidifier is blamed and the real cause of a natatorium problem is never discovered nor addressed. Chlorine odours, mould, condensation, or poor indoor air comfort, generally have causes unrelated to the dehumidifier. Instead, they may be due to building pressurization imbalances, improper vapour barrier, poor ventilation design, unbalanced water chemistry, or unsuitable architectural materials. They can also be related to inadequate maintenance, or perhaps just a slow, unnoticed degradation of operating parameters. Additionally, a few seemingly minor items missed during design and construction can also contribute to facility problems. Natatoriums have many unique design challenges and considerations that are not always obvious to anyone unsure about these facilities’ state-of-the-art requirements.

Without having an engineering background, one of the difficulties facility operators face is finding the true source of the problem, especially if there has been a long, gradual downward performance spiral. Some problems take a while to manifest and are not apparent until environmental conditions become unbearable or a visible deterioration occurs.

Chlorine odours can be a red flag

Any hint of chlorine odours in the facility’s non-pool areas is an indication of an undesirable, but easily corrected, building pressurization problem. Additionally, odours in adjacent spaces signal a natatorium air-side pressurization malfunction.

Under the guidelines of the American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE) standards for natatoriums, indoor pools are purposely designed with a slight negative building pressure. Negative pressure is created by exhausting more air than what is being introduced to satisfy the local code requirements for outdoor ventilation air.

Negative pressure (exhaust air) is also important because it ensures there is always some natatorium air, presumably containing some pool chemicals, being exhausted so it can be replaced with fresh outdoor air. This continuous dilution of the airborne chemicals helps ensure the best indoor air quality (IAQ) possible.

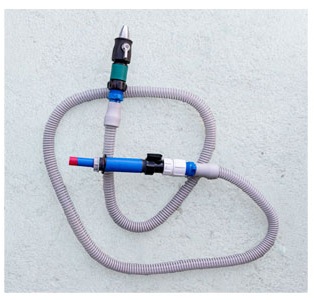

However, facility chloramine problems will generally not fully resolve the airborne chemical challenge with this ventilation approach alone as the source might be an underlying water chemistry problem. Further, trying to solve IAQ problems derived from water chemistry issues can be expensive in terms of conditioning excessive amounts of outdoor air. An appropriate balance of outdoor air and exhaust, to keep proper negative pressure, should be all that is necessary for proper IAQ if water chemistry is properly maintained. Persistent chloramine problems have a better chance at being resolved using water sanitation alternatives such as ultraviolet (UV) irradiation, sorghum moss, or a deck-level air capture exhaust system.

Since negative pressure is critical for indoor pools, heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) engineers ensure it is accomplished by specifying one or more exhaust fans in the ventilation system. The exhaust fan might be packaged with the dehumidifier, or mounted separately. Building operators should know where the exhaust fans are located.

Chlorine odours and eye irritation in the pool, or in non-pool areas, likely signifies a building pressurization problem, if pool chemistry and daily bather loads have not dramatically changed. In this case, the exhaust fan should be checked first. It may not be working properly or its original rating configuration (i.e. capacity to move air in cubic feet per minute [CFM]) has been changed. All it takes is one person fiddling with the exhaust fan or outside air dampers to create an imbalance of exhaust or outside air that leads to IAQ problems.

For example, a facility with a long history of chlorine odour problems in the pool area might have had someone decide that more outdoor air was needed to resolve the issue. Therefore, they open the outdoor air damper more and unbalance the entire system by creating a positive pressure environment. The IAQ problem remains unresolved and new complaints inevitably arise about pool odours residing in the facility’s other rooms.

As such, it is highly recommended that facility operators develop a solid understanding of the overall ventilation system’s air pattern. Equally important is the facility’s amount of outside ventilation air and exhaust air balance, which will not cure deck-level IAQ issues if the ventilation system is not delivering good quality air to the breathing zone. Therefore, some air delivery modifications might make a significant difference.