The dangers of summer waters: Why safer public pools are needed as open waters become more hazardous

by habiba_abudu | December 11, 2019 2:29 pm

By Terry Arko

[1]

[1]Shark attacks in the ocean, an alligator attack at a manmade lake at the Walt Disney World Resort in Bay Lake, Fla., brain-eating amoeba, flesh-eating bacteria, and some of the worst Cryptosporidium outbreaks at public pools… bathers were in tough waters, whether they were enjoying the open water or a pool at an aquatic facility. In fact, due to the worldwide stage, one of the most high-profile incidents of poor water quality occurred during the 2016 Summer Games in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, when two competition pools used for diving, water polo, and synchronized swimming, mysteriously turned green. In retrospect, the last few summers have been some of the strangest and most dangerous when it came to recreational aquatics.

Shark bait

[2]

[2]This author’s older brother has surfed in the same location at Huntington Beach in southern California for more than 30 years. One day, during the summer of 2018, he ventured into the dark emerald waters and spent the morning surfing. When he came in to shore to take a break, a lifeguard approached him and said, “Don’t go back out there.” The lifeguard told him they had spotted three great white sharks near the pier where he had just spent the morning surfing. The lifeguard also went on to say a woman had recently been attacked in the breaking waves at a near-by beach.

According to the Atlanta Journal-Constitution there were 107 shark attacks worldwide in 2017.1

The website Tracking Sharks (https://www.trackingsharks.com/2019-shark-attack-map) reports as of August 2019 there were 63 shark attacks worldwide with five fatalities. In fact, 50 per cent of the world’s shark attacks occur in Florida. While shark attacks are rare in Canadian waters, there have been reports of an increase in great white sharks off the coast of British Columbia. Also, a study conducted by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) in June 2014 stated the number of great white sharks off the coast of Eastern Canada has been on the rise since 2000.

Drought, warmer temperatures, and higher numbers of swimmers were considered to be some of the reasons for the increase of sharks in shallow water coastal areas.

Flesh-eating bacteria

In the summer of 2016, as tourists began flocking to the beaches, there were widespread reports of flesh-eating bacteria in the coastal waters from Texas to the panhandle of Florida. The culprit was Vibrio vulnificus, a nasty bacterium that invades the flesh, causing infections that can lead to amputation of limbs and even death.

Cases of this rare disease have been on the increase over the last few years, particularly in the brackish waters of bays and creeks near the ocean. According to several news reports, including one from the online publication The Guardian, there are many who believe the increase of the flesh-eating bacteria along the Gulf Coast is due to the chemicals used to clean up the BP oil spill (i.e. Deepwater Horizon) that occurred in 2010. As of August 2019, there were 13 cases of Vibrio vulnificus in the state of Florida (50 cases were reported in 2017). The bacteria are very active in warm saltwater coastlines.

It is important to understand, most cases of flesh-eating bacteria are related to open, warmer waters during the summer months. Pools that are properly maintained with correct water balance and sanitizer levels do not pose a threat.

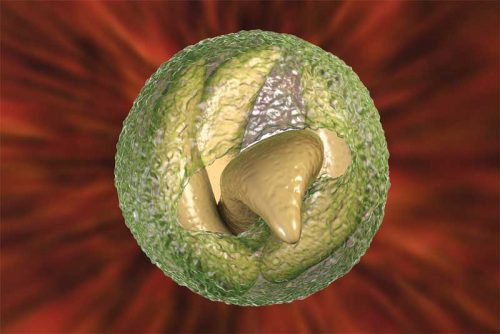

Brain-eating amoebas

[3]

[3]In the case of long hot summers, lakes will warm up continually throughout the season. Lakes and bays can become quite warm by the end of summer. Naegleria fowleri is an extremely lethal single-celled free-living amoeba that causes a rapid central nervous disease. It is commonly referred to as the brain-eating amoeba. According to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), little can be done to effectively stop the brain-eating amoeba once it enters the sinus and into the brain. In fact, more than 97 per cent of cases result in death. According to the Public Health Agency of Canada, there were 179 cases of Naegleria fowleri worldwide between 1996 and 2003.

Signs and symptoms of infection are like bacterial meningitis. Humans become infected when contaminated water enters through the nose and the amoeba travels to the brain. While cases are rare, most are fatal. This amoeba thrives in warm shallow untreated waters (mostly in lakes). The best way to avoid contracting the Naegleria fowleri amoeba is to avoid swimming in shallow warm areas. Most importantly, swimmers should not immerse their head or turn upside down in the water.

Typical chlorine levels in pools can help to inactivate Naegleria fowleri. Maintaining chlorine levels between one and three parts per million (ppm) along with a routine super chlorinating procedure—especially after adding fill water—should ensure protection from this parasite.

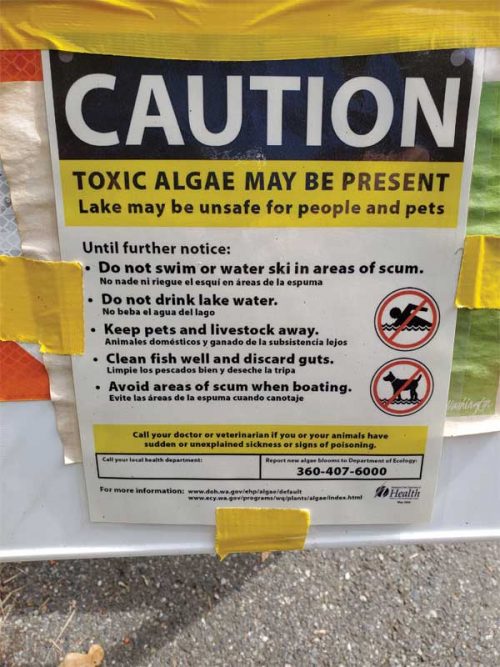

Toxic algae

[4]

[4]In August, MSN Lifestyle reported on a number of signs that were posted at lakes across the U.S. warning of toxic algae. Fed by rising water temperatures and nutrient-loaded fertilizer from farms an aggressive blue-green bloom takes over. These blooms can contain cyanobacteria which is toxic to humans and extremely harmful to dogs.

Toward the end of August, large portions of Lake Erie were marked as being unsafe for dogs to swim in. The CDC warns of paying attention to the signs of toxic algae. Swimmers and pet owners should be on the lookout for large floating mats of blue-green, brown, yellow, or red scummy looking algae. Usually, a rotting plant smell is present in these waters.

While shark attacks and brain-eating amoeba are all rare, they are virtually non-existent in pools. In fact, a properly treated and maintained pool remains one of the safest places to swim when it comes to the final dog days of summer. That said, there are some things that can be problematic in pools and, as a result, can potentially tarnish the industry’s reputation.

Recreational Water Illnesses (RWIs)

By doing some research, one will find the most common and widespread RWI that occurs is Cryptosporidium (Crypto). It is a parasitic pathogen that is contained within a hard, egg-like cyst, which makes it highly resistant to chlorine. In fact, according to the CDC, Crypto can remain active in regular chlorine levels of 1 ppm for up to 10 days. It is between four and six microns in size, which enables it to pass through most filters used in public pools. Crypto is an infectious organism that is transferred fecal/orally. It makes its way into pool water via swimmers who are ill with diarrhea. One very small deposit from an incontinent bather can lead to millions of Crypto parasites being introduced into the water. If tainted water is swallowed, it will only take 10 Crypto parasites to cause infection and illness.

When is the potential for an outbreak highest in a public pool?

[5]

[5]According to research, the most outbreaks occur from mid-to-late summer when the temperatures heat up and increased numbers of swimmers visit the pool. There are not any foolproof ways to completely ensure Crypto will not invade a pool; however, there is a layer of procedures that can help ensure protection.

First and foremost is educating bathers on the importance of good hygiene, including not swimming for two weeks after being ill with diarrhea. Also, cleansing showers before entering the pool should be required, and for small children frequent bathroom breaks should be practised. Proper chlorination should always be maintained between 1 and 4 ppm. The addition of a secondary sanitizer system (e.g. ozonator or ultraviolet [UV] unit) should also be incorporated. While both of these are supplemental systems, both are more effective at inactivating Crypto than chlorine.

Further, there are now advanced oxidation process (AOP) devices available, which create hydroxyl radicals that can effectively inactivate Crypto and work well with low levels of chlorine. Lastly, incorporating an enhanced filtration method through the use of a natural-based clarifier flocculant can help remove the parasite and keep it out of the pool and away from bathers. This same practice is used at drinking water facilities to help sand filters remove the smaller micron Crypto and hold it until it inactivates and can be backwashed out of the system.

Crypto remediation

[6]

[6]If a diarrheal discharge occurs, it is most likely that Crypto has entered the pool. The CDC’s recommended remediation process is as follows:

- Clear all persons from pool;

- Adjust the pH of water to 7.5 or less;

- Maintain the water temperature at 25 C (77 F); and

- Raise and maintain the chlorine level at 20 ppm.

All of the above must be sustained for 12.75 hours to effectively inactivate Crypto in a pool without cyanuric acid stabilizer (CYA). According to the CDC and the Model Aquatic Health Code (MAHC), if a pool has levels of CYA between 1 and 15 ppm then the chlorine level needs to be raised to 20 ppm and held for 28 hours to ensure the Crypto has been inactivated. That said, it is important for an aquatic facility director or pool operator to know if CYA stabilizer is in the pool and at what level.

[7]

[7]Some public pool operators use tri-chlor chlorine tablets as the primary sanitizer. These are stabilized chlorine tablets that contain CYA. In this case, some operators may not be aware of the amount of CYA stabilizer in the pool as a result of using these tablets. For every 10 ppm of chlorine provided from tri-chlor 6 ppm of CYA is introduced into the water. Further, CYA does not breakdown, the levels only increase.

More recent research by the Committee of The Model Aquatic Health Code (CMAHC) has shown that increased levels of CYA reduce the effectiveness of chlorine to inactivate pathogens such as Crypto. In fact, research by the council’s ad hoc committee shows people are just as likely to get ill from Crypto in water with 0 ppm of free chlorine (FC) as they are in a pool with 1 ppm free chlorine and 100 ppm CYA. Based on this, it is imperative that an un-stabilized form of chlorine be used to raise the chlorine level for a Crypto remediation process. Liquid chlorine is highly recommended as it is fast acting, economical, and will not increase CYA levels or calcium hardness.

Keeping pools safe

Swimming is one of the most popular sports and leisure activities in Canada and the United States with millions of people visiting aquatic facilities every year. As the public hears more news on the risk and dangers of swimming in open waters, many will turn to commercial pools and aquatic centres as a safe refuge. Pool operators and service technicians may not need to worry about sharks or toxic algae in pools; however, keeping them safe and sanitary for swimmers can still pose a challenge. That said, knowledge along with proper chemistry can go a long way toward keeping water safe.

[8]Terry Arko is a product training consultant for HASA Pool Inc., a manufacturer and distributor of pool and spa water treatment products in Saugus, Calif. He has more than 40 years’ experience in the pool and spa/hot tub industry, working in service, repair, retail sales, chemical manufacturing, technical service, commercial sales, and product development. He has written more than 100 published articles on water chemistry and has been an instructor of water chemistry courses for more than 25 years. Arko serves as an observer on the board of the Recreational Water Quality Committee (RWQC) and is a member of the Council for the Model Aquatic Health Code (CMAHC). He is a Commercial Pool Operator (CPO) course instructor, a teacher of the Pool Chemistry Certified Residential course for the Pool Chemistry Training Institute (PCTI), and a member of Pool & Spa Marketing’s Editorial Advisory Committee. Arko can be reached via e-mail at terryarko@hasapool.com[9].

[8]Terry Arko is a product training consultant for HASA Pool Inc., a manufacturer and distributor of pool and spa water treatment products in Saugus, Calif. He has more than 40 years’ experience in the pool and spa/hot tub industry, working in service, repair, retail sales, chemical manufacturing, technical service, commercial sales, and product development. He has written more than 100 published articles on water chemistry and has been an instructor of water chemistry courses for more than 25 years. Arko serves as an observer on the board of the Recreational Water Quality Committee (RWQC) and is a member of the Council for the Model Aquatic Health Code (CMAHC). He is a Commercial Pool Operator (CPO) course instructor, a teacher of the Pool Chemistry Certified Residential course for the Pool Chemistry Training Institute (PCTI), and a member of Pool & Spa Marketing’s Editorial Advisory Committee. Arko can be reached via e-mail at terryarko@hasapool.com[9].

Notes

1 See “Why shark attacks could be on rise around the world,” published by The Atlanta Journali-Constitution on April 6, 2019. For more information,visit https://www.ajc.com/news/national/why-shark-attacks-could-the-rise-around-the-world/BBeH5zATHFszvTqxm9km4K/. (Accessed on September 12, 2019)

- [Image]: https://www.poolspamarketing.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/bigstock-Happy-Family-Mother-Baby-So-264759913.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.poolspamarketing.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/20190825_113716.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.poolspamarketing.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Lake_Okeechobee_algal-bloom.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.poolspamarketing.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/bigstock-Great-White-Sharks-77919812.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.poolspamarketing.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/bigstock-220937452.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.poolspamarketing.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/bigstock-Release-Of-Sporozoites-From-Cr-275519563.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.poolspamarketing.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/bigstock-Bacterium-Vibrio-Vulnificus-312902200.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.poolspamarketing.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Arko_Headshot.jpg

- terryarko@hasapool.com: mailto:terryarko@hasapool.com

Source URL: https://www.poolspamarketing.com/trade/features/case-studies/the-dangers-of-summer-waters-why-safer-public-pools-are-needed-as-open-waters-become-more-hazardous/