Incorporating recommendations for safe aquatic activity

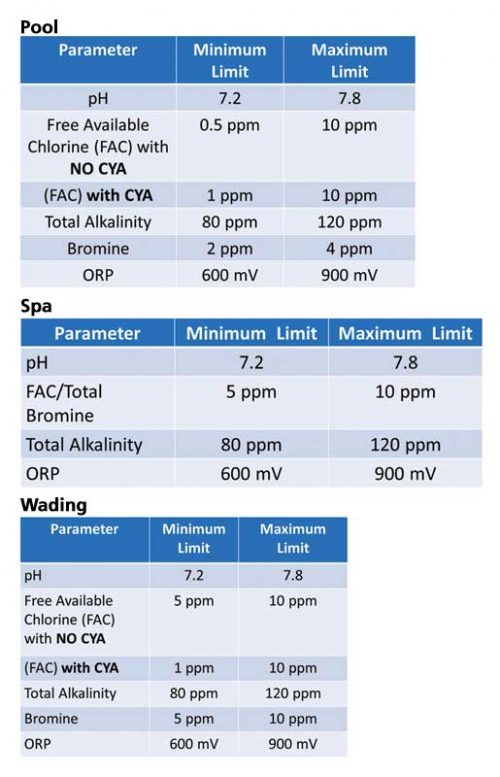

Based on scientific research and best practices, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has developed the Model Aquatic Health Code (MAHC) to make swimming and other aquatic activity safer and healthier.7 The new Public Pool Regulation 565 incorporates many requirements from the MAHC. For example, the introduction of maximum disinfectant concentration was derived from the model code. Chemical disinfectants, such as chlorine and its products, are powerful oxidizing agents that destroy harmful microbes. Exposure to high concentrations of these chemicals and their byproducts in pools, spas, and wading pools can be harmful to human health as well as the environment. Operationally, chemically balanced water not only prevents corrosion and scaling-related damage to property, but it is also necessary for optimal disinfection power and, therefore, there is the need for lower and upper chemical concentration limits.

The modernized regulation has incorporated many recommendations made by the Office of the Chief Coroner for Ontario as well. A coroner’s inquiry in 2009 following a drowning, recommended the requirement for a buoyline in all unsupervised Class B pools where the slope exceeds eight per cent. The intent of the recommendation was to provide a lifeline to a distressed swimmer. Adopted by the Ontario Building code, this requirement is new to the Public Pool Regulation 565.

Additionally, the admission standards for public pools—another recommendation which is now included in the public pool regulations—requires the presence of a guardian (e.g. parent) or supervisor and a swim test for young children. The requirement intends to reduce the risk of drowning deaths and injuries by maintaining adequate surveillance over the whereabouts and the activities of young bathers while they are inside the pool enclosure. To achieve this, the regulation now requires Class A pool operators to have a mandatory process in place to ensure a guardian or designated person supervision of children less than 10 years of age. This process must include:

- a swimming competency test for a child under 10; and

- a method of communicating the requirements of the process (e.g. a wristband).

To establish this critical safety requirement, pool owners and operators should consult with water safety experts on best practices, such as standardized swim competency tests.

The regulation is now more flexible in recognizing lifeguard and assistant lifeguard qualifications. It acknowledges there are credible organizations, in addition to the Lifesaving Society, that train and certify lifeguards/assistant lifeguards. Organizations that wish to have their lifeguard/assistant lifeguard certification approved by MOHLTC can now apply directly to the ministry. To enable such approval, MOHLTC has developed an Ontario lifeguard and assistance lifeguard training standard based on currently accepted international and North American standards for which lifeguard training certificates will be evaluated to determine their acceptability.

Conclusion

Public health regulations, including the modernized Ontario Public Pool Regulation 565, are designed to protect public health and safety by establishing province-wide minimum standards. With the modernization process complete and the new pool regulation in place, the stage is set in Ontario for all stakeholders, including the recreational water industry and public health units, to work together to help make aquatic facilities healthy and safe. This is possible through ongoing collaboration between all parties involved in the modernization process and continued improvement of the regulation in tandem with the future evolution of the recreational water industry.

Notes:

1 See “Canadian Drowning Report 2018 edition,” prepared for the Lifesaving Society Canada by the Drowning Prevention Research Centre Canada. For more information, visit www.lifesavingsociety.com/media/291819/2018%20canadian%20drowning%20report%20-%20web.pdf. (Accessed on Oct. 16, 2019)

2 See “Cryptosporidium outbreaks associated with swimming pools,” by Steven Lam, Bhairavi Sivaramalingam, and Harshani Gangodawilage (all authors contributed equally to the paper), published on the web by Environmental Health Review on May 30, 2014. For more information, visit https://pubs.ciphi.ca/doi/full/10.5864/d2014-011. (Accessed on Oct. 16, 2019)

3 See “A Review and Update on Waterborne Viral Diseases Associated with Swimming Pools,” by Lucia Bonadonna and Giuseppina La Rosa, published online by the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health on Jan. 9, 2019. For more information, visit www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/16/2/166/htm. (Accessed on Oct. 16, 2019)

4 See “6 people injured after exposure to noxious fumes in Etobicoke,” posted by CBC News on May 17, 2014. For more information, visit www.cbc.ca/news/canada/

toronto/6-people-injured-after-exposure-to-noxious-fumes-in-etobicoke-1.2646518. (Accessed on Oct. 16, 2019)

5 See “Guidelines for Safe Recreational Water Environments,” published by World Health Organization in 2003. For more information, visit https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/42591/9241545801.pdf;jsessionid=1210B195237782D6FD32CCC043D963EF?sequence=1. (Accessed on Oct. 16, 2019)

6 See “Recreational Water Protocol, 2018,” published by the Population and Public Health Division, Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (effective: January 1, 2018 or upon date of release). For more information, visit www.health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/publichealth/oph_standards/docs/protocols_guidelines/Recreational_Water%20Protocol_2018_en.pdf. (Accessed on Oct. 16, 2019)

7 See the “2018 Model Aquatic Health Code & Annex,” published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. For more information, visit www.cdc.gov/mahc/editions/index.html. (Accessed on Oct. 16, 2019)

Mahesh Patel, CIPHI(C), is a health hazard manager with Toronto Public Health (TPH). He holds a M.Sc. in water environmental management, a B.Sc. (honours) in applied chemistry, and a BAA in environmental health. As the safe water lead, he is responsible for both drinking and recreational water quality. This includes monitoring drinking water, beach water, and the compliance inspection program for public pools, spas/hot tubs, and wading pools. As the legal and enforcement lead, Patel has played a major role in the development and implementation of policies and procedures. Internally he provides ongoing enforcement training and support to staff, while externally he continues to provide assistance and training to other Ontario health units and agencies for which he received an award of excellence from the Canadian Institute of Public Health Inspectors (CIPHI) in 2012. He can be reached via e-mail at mpatel@toronto.ca.

Mahesh Patel, CIPHI(C), is a health hazard manager with Toronto Public Health (TPH). He holds a M.Sc. in water environmental management, a B.Sc. (honours) in applied chemistry, and a BAA in environmental health. As the safe water lead, he is responsible for both drinking and recreational water quality. This includes monitoring drinking water, beach water, and the compliance inspection program for public pools, spas/hot tubs, and wading pools. As the legal and enforcement lead, Patel has played a major role in the development and implementation of policies and procedures. Internally he provides ongoing enforcement training and support to staff, while externally he continues to provide assistance and training to other Ontario health units and agencies for which he received an award of excellence from the Canadian Institute of Public Health Inspectors (CIPHI) in 2012. He can be reached via e-mail at mpatel@toronto.ca.