Safer recreational waters: Ontario’s Public Pool Regulation improved to ensure public health and safety

Recreational water activities are a great way for people to stay active and relax. Owners and operators of pools and spas/hot tubs must be mindful of the potential health hazards, injuries, infections, and in extreme cases, death. The Lifesaving Society, a charitable organization working to prevent drowning and water-related injury, reported 297 and 293 water-related fatalities in Canada in 2016 and 2017, respectively.1 A total of 210 recreational-water-related deaths were recorded in Ontario for the same period.

Water contamination and diseases

Recreational water facilities include pools, spas, wading pools, and splash pads. These facilities are subject to microbial contamination because bathers can introduce disease-causing germs such as bacteria, viruses, parasites, and fungi into the water.

Further, warm temperatures and rapid water turbulences in spas provide ideal conditions for germs to grow and multiply, leading to the spread of ailments like Legionnaires’ disease. Many disease outbreaks, such as cryptosporidiosis,2 pseudomonas, human enteric viruses (adenovirus, enterovirus),3 and fungal skin infections, such as athlete’s foot, can originate from pools, spas, and wading pools. These diseases are often transmitted when otherwise healthy bathers accidentally swallow contaminated water, inhale tainted mist droplets, or come in direct contact with dirty surfaces. Young children, the elderly, and those with weak immune systems are most likely at risk when exposed to harmful germs.

Pool hazards

A malfunctioning filtration system and inadequate disinfection methods can cause microbes to grow and multiply quickly. In the recent past, failing/faulty equipment has caused occupational injuries to workers and resulted in serious harm to bathers due to chlorine inhalation. Not long ago, the release of chlorine gas in a pool enclosure resulted in one serious injury and evacuation of the facility.4

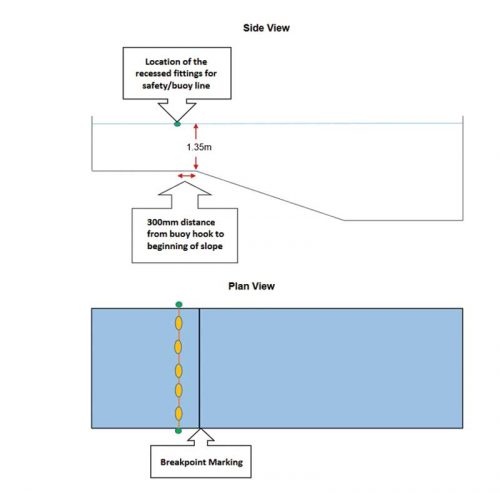

Water features like powerful pumps, which are used for recirculating water through filtration systems, can be a source of serious injury. There are also a number of other potential health and safety hazards associated with recreational water facilities. For example, drownings can occur at any water depth and shallow water dives can result in serious debilitating head and spinal injuries, and even death.

Protecting public health

The World Health Organization (WHO) recognizes the hazards present in recreational aquatic environments as a public health concern and has published a two-part guideline5 that is the basis of standards and regulations designed to control health risks associated with recreational waters. Indeed, countries across the world, including the federal, provincial, and state governments of Canada and the United States, have proactively regulated public aquatic facilities accordingly.

In Ontario, pool regulations and guidelines for spas and wading pools date back to mid-1900s and earlier. Under the Ontario Health Protection and Promotion Act (HPPA), local boards of health (BOH) are required to deliver public health programs and services. The ‘Safe Water Program’ standard aims to “prevent and reduce the burden of water-borne illnesses and injuries related to recreational water use.” The Recreational Water Protocol, 20186 provides BOHs direction on how to properly operationalize the requirements outlined in the standard. One such requirement for BOHs is to ensure aquatic facilities meet the regulated minimum health and safety standards as set out in the modernized Public Pool Regulation 565 and Recreational Camps Regulation 568.

Pools and spas have evolved since the 1940s when the regulations were last revised. Advances in technology and design concepts, among other things, have led to several innovations in the recreational water industry. Familiar definitions of aquatic environments have increasingly blurred and hybrids like swim spas have become more common.