Strategies for chloramine removal: Best practices for maintaining proper air and water quality at indoor pools

Indoor recreational water facilities across North America see millions of visitors a year enjoying swimming, soaking, and just plain fun during the colder seasons. Whether it is at a pool, spa, or hot tub at a ski resort, waterpark, hotel, YMCA, or municipal facility, there are plenty of opportunities for family aquatic fun. However, all this activity can put a strain on the water and air quality within the aquatic venue. Dealing with these issues, particularly at an indoor facility, can be a daunting task. These issues can affect the comfort of bathers/swimmers, as well as the health of the staff that are there for longer periods.

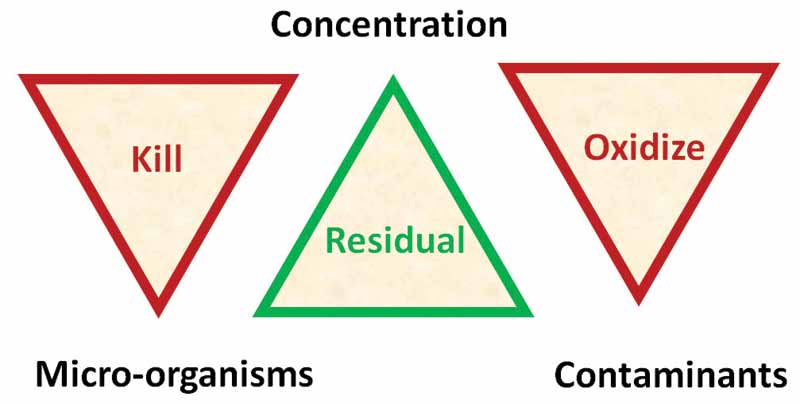

Chloramines are formed when free chlorine reacts with perspiration, urine, and other nitrogen-containing contaminants that are introduced into the water which create a demand on the free chlorine. Free chlorine reacts with these contaminants to produce chloramines, also known as combined chlorine, that created a demand for free chlorine. When this reaction is allowed to progress, some of the chloramines produced are volatile and gas-off creating poor air quality, which leads to bathers/swimmers complaining about stinging eyes, nasal irritation, or difficulty breathing within the aquatic facility.

Many people think this odour is a result of too much chlorine; however, what it really means is too much combined chlorine. Some volatile chloramines, along with high humidity, also contribute to the corrosion of metal components within the aquatic venue. Chloramines can also be introduced into the aquatic environment via the domestic fill water added to the pool, as some municipalities use chloramination for disinfection.

Chloramines can exist either as monochloramine (NH2Cl), dichloramine (NHCl2), or trichloramine (nitrogen trichloride [NCl3]). The NCl3, according to White’s Handbook of Chlorination and Alternative Disinfectants, “is easily aerated because of its low solubility in water.” NCl3 is the volatile substance that is irritating to the eyes and nose of bathers/swimmers and corrosive to structural metallic components of the venue. The effects of trichloramine are even more pronounced in a confined, humid room where little or no air is circulated.

When free chlorine reacts with organic substances it creates organic chloramines which are much more difficult to remove from the water than inorganic, ammoniated, or nitrogen-based chloramines. Any chlorine-based compound resulting from this reaction is called a disinfection byproduct (DBP). DBPs include organic compounds found in body lotions (e.g. deodorants and sunscreens), bathing garments, various body fluids, and fecal matter on the bather. DBPs also form when free chlorine reacts with fecal coliform bacteria, creatine, L-histamine, chloroform, and excess medication found in urine, along with the urea found in urine itself. While it is known these compounds exist at this point in time, it is not known at what levels they become toxic in an aquatic venue. Competitive swimmers and pool personnel may be at greater risk for inhalation of volatile substances as they remain in the aquatic environment for longer periods of time than the average bather/swimmer.

While there are many strategies for dealing with this problem they fall into several distinct groups; chemical treatments, supplemental sanitizers, filter additives, and, lastly, heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) systems.

In Germany and in other European countries, the chlorine used to deal with bather demand is kept low, usually below 0.5 parts per million (ppm). This low chlorine residual is maintained because of the use of supplemental sanitizing systems that can achieve the same or better oxidative or disinfectant results. With a low free chlorine level, combined chlorines simply cannot form in concentrations higher than the available chlorine despite the concentration of ammonia. Ozone and chlorine dioxide are examples and are strong oxidizers and sanitizers that can be used to supplement the chlorine. In North America, the use of ozone, ultraviolet (UV)-C light, and advanced oxidation process (AOP) are examples of strong oxidizers that can be used to supplement the chlorine in the pool.