Identifying soil types and compaction of soil subgrades

By Brian Burton

Understanding soils as they relate to interlocking concrete paver (ICP) installation is vital to a successful project. Identifying soil types and knowing what effect each one can have on project length and labour requirements is also imperative. Further, knowing the soil type and achieving an adequate level of compaction is integral to the long-term performance of an installation and can often help reduce unnecessary callbacks.

Gradation fundamentals, sieve analysis

Generally, the suitability of a soil for use under a pavement decreases with its particle size. The measurement of various particle sizes is called soil gradation and is accomplished via a series of sieves. These circular sieves have various size openings to allow any material smaller than screen size to pass through. Soil samples are dried, weighed, and then placed in the coarsest sieve, while stacked over increasingly finer sieves. As they are shaken, each one blocks a specific size particle (or larger) from passing to the next smaller sieve, while smaller particles pass to the next smaller sieve, and so on. The material remaining on each sieve is weighed and the per cent passing each is calculated.

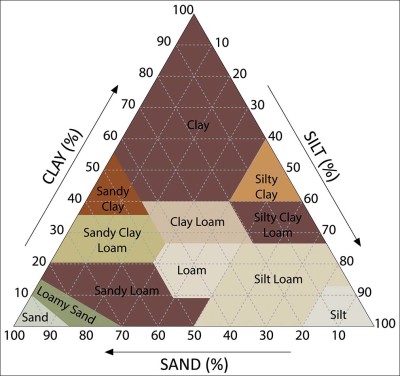

Classification of soils by this gradation technique indicates how it will perform under a pavement. (Aggregate base materials and bedding sands are also classified by gradation.) A sieve analysis typically produces particle sizes that fall into the following soil categories. Most soils are a mix of the following different sized particles:

- Coarse sand: 2 to 0.25 mm (0.0787 to 0.0098 in.)

- Fine sand: 0.25 to 0.076 mm (0.0098 to 0.003 in.)

- Silt: 0.076 to 0.005 mm (0.003 to 0.000196 in.)

- Clay: Smaller than 0.005 mm (0.000196 in.)

Soil classification

Most contractors should be familiar with the general soil variations in their area; however, there can be significant soil type differences within a small geographic area. When a soil classification is known, its tendency to hold water and ease of compaction can be predicted. Identifying soil types also assists contractors when selecting compaction equipment and when estimating the time needed to complete a project. For example, a heavy clay soil may require more time to excavate and compact than a sandy soil.

Quick field identification

A simple way to classify soils in the field is by visual appearance and feel. If coarse grains can be seen and the soil feels gritty when rubbed between the fingers, then it is likely a sandy soil. If grains cannot be seen with the naked eye and it feels smooth, then the soil is likely a silt or clay.

A primary factor in the performance of soil under pavement is its ability to hold water. The more water the soil will hold, the poorer it performs as a foundation for pavement. There are some easy ways contractors can perform quick field identification and assess the soil’s water holding capacity.

Patty test

- Mix the soil with enough water to make a patty of putty-like consistency and let it dry completely.

- The greater the effort required to break the patty with fingers, the greater the plasticity, or ability to hold water. High-dry‑strength is characteristic of clays, while silts and silty sands will break easily.

Shake test

- Mix one tablespoon (15 ml [0.5 oz]) of water with the soil sample by hand. (The sample should be soft, but not sticky.)

- Shake or jolt the sample in a closed palm a few times.

- If water comes to the surface, the soil is fine sand.

- If no water or very little moisture comes to the surface, it is silt or clay.

- If squeezing the soil between the fingers causes the moisture to disappear, the soil is sandy.

- If moisture does not readily disappear, then the soil is silty.

- If moisture does not disappear at all, the soil is clay.

Snake test

- Moisten a small sample of soil to the point where it is soft, but not muddy or sticky.

- Roll the sample into a thread or ‘snake’ between the palms.

- The longer the thread can be rolled without breaking, the higher the clay content.

These field tests can be performed quickly and easily to classify soils and obtain a relative measure of their water holding capacity. In cases where a contractor is unsure, or unable to classify the soil, a civil or geotechnical engineer should be hired to test and/or determine the exact soil classification.