Empowering public health inspectors to enforce regulations

by Sally Bouorm | March 1, 2014 9:29 am

By Mahesh Patel

[1]

[1]Public swimming pools and hot tubs are an important source of healthy recreational activity. There are an abundance of these facilities in Canada, and Ontario is no exception. Swimming is one of the best forms of aerobic exercise—a swimmer uses multiple muscle groups, it is easy on joints, and it strengthens the heart. A few minutes in a hot tub can relax tense muscles, ease stress, and be a great source of enjoyment.

Today, sedentary work and play continues to replace physical activity. Recent studies have found children are particularly at risk due to inactivity and they tend to be less fit than their parents were at the same age. Therefore, swimming pools and hot tubs have an important recreational role within society. However, it is also important to remember their inherent dangers, e.g. drowning, spread of disease, and other various injuries.

Provincial, territorial, and state governments across Canada and the U.S. have taken measures to protect public health and safety by reducing the risks associated with the use of swimming pools and hot tubs. In Canada, for instance, owners and operators of these public facilities are responsible for maintaining minimum standards necessary to protect health and safety and the well-being of bathers. Further, building code and health regulations for public swimming pools and hot tubs in Ontario specify minimum requirements.

Ontario enacts swimming pool and hot tub regulations

Ontario’s Ministry of Health & Long Term Care (MOHLTC) has enacted the Public Pools regulation (565.90) and the Public Spas regulation (428/05) under the Health Protection and Promotion Act (HPPA).

The responsibility to enforce these regulations lies with the local medical officer of health. The regulations set out the minimum requirements necessary to protect the health and safety of those using these facilities. They are prescriptive in nature and compel owners and operators of such public facilities to meet all specified requirements within the regulations. Frequencies of facility inspections are mandated under the Recreational Water Protocols by the MOHLTC.

Public health inspectors (PHIs) in environmental health sections of the local public health units have the responsibility to inspect and enforce public swimming pool and hot tub regulations. Their mandate is to inspect them at least two times per year and no less than every three months while these facilities are operating. Outdoor facilities are inspected twice during the summer operating season and indoor facilities must be inspected quarterly.

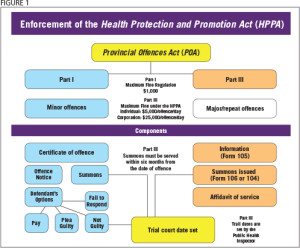

PHIs use strategies such as progressive enforcement and legislative tools set out in laws such as the Ontario Provincial Offences Act (POA) and the Ontario Health Protection and Promotion Act (HPPA) to address infractions. This article is a discussion of some of the main enforcement issues encountered by PHIs in carrying out this important task. It further highlights aspects of progressive enforcement as a strategy and the use of the POA Part III, Commencement of Proceeding By Information[2], in conjunction with HPPA as an enforcement tool.

Key enforcement issues

[3]

[3]Non-compliance of swimming pool and hot tub regulations gives rise to two main types of violation—minor and major infractions. Minor offences are not likely to have any health and safety consequences. For example, a facility operator who is not keeping daily records is unlikely to impact on the health and safety of bathers; however, this is regarded as non-compliance of the public pool regulations.

On the other hand, major infractions such as a missing or inoperable emergency phone are critical and likely to have serious consequences on bather health and safety. Similarly, infractions such as low or no chlorine (Cl)/bromine (Br) disinfection levels caused by a malfunctioning dosing device are also likely to have a serious impact on health and safety if not corrected in a timely manner.

| PROVINCIAL AND TERRITORIAL PUBLIC SWIMMING POOL AND HOT TUB REGULATIONS |

|---|

| Alberta http://www.health.alberta.ca/documents/Standards-Pools.pdf[4] British Colombia www.health.gov.bc.ca/protect/pdf/bc-pool-operations-guidelines.pdfManitoba[5] http://web2.gov.mb.ca/laws/regs/pdf/p210-132.97.pdf[6]New Brunswick http://canlii.ca/en/nb/laws/regu/nb-reg-81-126/latest/nb-reg-81-126.html[7]Newfoundland http://assembly.nl.ca/Legislation/sr/regulations/rc961023.htm[8]Ontario Swimming pools: http://www.e-laws.gov.on.ca/html/regs/english/elaws_regs_900565_e.htm[9] Spas/hot tubs: http://www.e-laws.gov.on.ca/html/regs/english/elaws_regs_050428_e.htm[10] Prince Edward Island Quebec Saskatchewan Northwest Territories |

Minor offences

In the enforcement of minor offences, PHIs are, in some ways, incapacitated because they do not have the ability to issue set fines in the form of POA Part I, Commencement of Proceedings By Certificate of Offence [15](ticket), which are available for other regulations. Ticketing is a quick and easy way to issue a pre-set fine for a specified section of a regulation. The benefit of ticketing is it does not involve complicated, time-consuming processes. Although PHIs always have the option of compelling an offender to court by issuing a POA Part III, Summons, this option is not always exercised for minor offences because of its more involved processes, but more importantly, the outcome often does not justify the effort. As a result, reoccurring minor violations of swimming pool and hot tub regulations often remain unenforced.

Major offences

With major offences, where the risk of a critical injury or a fatality is real, repeat infractions are addressed in two ways. For offences posing an immediate danger to the health and safety of bathers, PHIs invariably use HPPA section 13[16] closure orders to effectively remove people from immediate danger, thus preventing exposure to any potential health hazards. Aquatic facility owners/operators who have been served with such closure orders must immediately remove bathers from the swimming pool/hot tub area and close the facility immediately. The facility must remain closed until the health hazard/potential health hazard has been removed or rendered ineffective and danger to bathers is averted.

Further, PHIs are required to re-inspect the facility to ensure compliance with the regulation and ensure the condition(s), which resulted in the closure order, have been corrected. Unfortunately, closures do not always result in ongoing compliance and there are recurrent violations. To change the behaviour of the aquatic facility owner/operator, and to prevent major violations from recurring, enforcement action should ideally be the next step. This involves issuing the offender a summons under the provisions of POA Part III for the violation of the regulation, which requires them to appear in provincial court.

PHIs have two options when issuing a charge under POA Part III. They may either issue a charge for a specific section of the regulation or a more general charge for failure to comply with the regulation. In most cases, PHIs use the former option and issue a charge specific to the section of the regulation. Although charges for the specific section of the regulation do result in convictions, they often do not result in the intended behaviour change. This is primarily because courts consider each conviction independently of other similar, but not identical to previous convictions. This effectively prevents prosecutors from using previous convictions to request heavier penalties at the time of sentencing, resulting in the courts issuing much lower fines.

[17]

[17]Often, a low fine is regarded by facility owners/operators as a cost of doing business and, therefore, does not change their behaviour with respect to regulation compliance. For each subsequent major health hazard the closure order averts the danger and the low fines negate further court action by PHIs. This may explain why there is minimal enforcement of major offences of public swimming pool and hot tub regulations in Ontario.

Enforcement strategies

The aim of any enforcement action is to encourage a change in the offender’s behaviour to achieve compliance with the law. There are enforcement strategies available to Ontario health units that can be used to resolve the enforcement obstacles PHIs encounter. These strategies can achieve the ultimate goal of enforcement action by changing the behaviour of public swimming pool and hot tub owners/operators such that they take the corrective actions necessary to meet the regulations to protect public health.

Taking a progressive approach

Progressive enforcement is a good alternative strategy. Just as the name suggests, it is somewhat similar to the concept of progressive discipline. With this strategy, punishment increases proportionately based on the severity and number of offences committed. Progressive enforcement begins with education. For example, when a swimming pool owner/operator does not comply with the regulation, the PHI would, without the threat of enforcement action, make every effort to inform the operator of the regulation requirements, the possible reasons for non-compliance, as well as discuss what needs to be done to achieve compliance.

[18]

[18]The PHI would allow perhaps more than one opportunity to comply. If that does not result in the desired modification in the behaviour of the owner/operator, and ultimately compliance with the regulation, then the next step would be issuing a POA Part I ticket (where available).

Subsequent non-compliance would result in the progressive escalation of enforcement actions. For instance, a POA Part III charge would be issued, and upon conviction, a substantial fine would be requested along with a probation order. In the case of a corporate owner, a prohibition order and piercing of the corporate veil would be pursued. Each progression would result in increasingly heavier penalties until the desired change of the offender’s behaviour is achieved.

Progressive enforcement involves the use of various laws and the powers granted under them in a sequence to achieve the desired outcome. This is best illustrated by the following case study.

A case of non-compliance

This case study involves a class B indoor swimming pool owned by a corporation registered under the Ontario Corporations Act (corporate owner) located in a multi-residential apartment building. The swimming pool is unsupervised and serves residents of 30 units.

Over the span of two years, the swimming pool has been inspected eight times by the local public health unit. Of the eight inspections, six have resulted in re-inspections due to violations that were considered significant—meaning the offences could have, if not corrected in a timely manner, impacted the health and safety of bathers. The list of violations also included multiple minor infractions that were not serious enough to warrant immediate closure.

Upon each re-inspection, despite the swimming pool operator fixing the problems which led to the significant violation, multiple minor infractions, including proper pool size and depth markings and poor daily record keeping, remained uncorrected.

After each inspection, the PHI reviewed the violations with the swimming pool operator and discussed the reasons for non-compliance. The operator was then provided with an inspection report, which identified all violations, and provided direction on what needed to be done to achieve compliance within a specified timeframe. At the time of each re-inspection, the PHI further provided the operator with a completed inspection report, which again identified the remaining minor infractions that were still in non-compliance. Although the operator complied with the requirements of the infractions considered to be significant (major), minor violations were ignored over several inspections and re-inspections.

The PHI made every effort to educate the operator on the importance of compliance with all regulations, including minor infractions. As often encountered by PHIs, this operator provided the inspector with a litany of excuses as to why the infractions were not fixed and promised to comply by the next inspection.

To affect change in the behaviour of this swimming pool operator, the public health unit decided to pursue a progressive enforcement strategy. In doing so, it used the provisions under HPPA sections 100 and 100(4), and POA Part III. HPPA section 100 identifies all offences under the act, and Section 100(4), states “any person who contravenes a regulation (under this act) is guilty of an offence.”

In legal terms, a ‘person’ can be an individual, such as an operator of a swimming pool/hot tub, or a company that is a corporation registered under the Ontario or federal corporations act (corporate owner). Therefore, in this case, both the operator and the corporate owner of the swimming pool could have been charged for maximum impact in achieving behaviour change. However, after due consideration, the corporate owner of the swimming pool was charged and a summons was issued to its director. The wording of the charge on the summons included the offence and read: “owner failed to keep signed records setting out free available chlorine and total chlorine as required by section 8(a) of the Public Pools Regulation 565” and the charge was made contrary to HPPA section 100(4).

The corporate owner challenged the charge and the case went to trial. At the trial, the PHI provided testimonial evidence under oath supported by documentary evidence, which included inspection/re-inspection reports, photographs, and a certified corporate profile report. The defence council did not call his client to provide evidence. After reviewing the evidence, the justice of the peace presiding over this case found the corporate owner of the swimming pool guilty as charged and levied a $500 fine.

Case study discussion

At first glance, a $500 fine for a large corporation seems insignificant and, therefore, an unlikely deterrent. The strategy to convict a corporation or an individual such as a swimming pool/hot tub operator, under the HPPA using POA Part III, however, sets the path for progressive enforcement.

[19]

[19]It is also important to note, maximum fines allowable under HPPA convictions using POA Part III for individuals is $5,000 and $25,000 for corporations. In both instances, the fines are per day, per offence (See figure 1.). This method of charging a repeat offender substantially increases the possibility of attaining much heavier fines at the time of subsequent convictions, even for minor offences. It further enables prosecutors to seek probation/prohibition orders against the offender.

As a comparison, the maximum fine for a charge under the regulation using only POA Part I (ticket) is $1,000. Further, because convictions are recorded under individual sections of the regulation, previous convictions cannot be used by prosecutors during sentencing to show reoccurrence of violations and convictions. This inevitably results in much smaller penalties and prevents the use of probation/prohibition orders.

[20]

[20]For the purpose of this discussion, assuming the corporate owner of this class B indoor swimming pool continued to commit minor infractions and was therefore non-compliant with the regulation, to progressively escalate enforcement to the next stage, PHIs now have the option to charge both the corporate owner and the operator of the swimming pool for failing to comply with Public Pool Regulation 565, under section 100(4) of the HPPA. Upon conviction, the prosecutor in this case can apply the previous conviction(s) and demonstrate to the court the defendant’s behaviour remains unchanged and, therefore, warrants a heftier fine. At the same time, however, the prosecutor may put the corporation’s officers, including directors, secretaries, managers, and even responsible employees on notice that they may be personally liable to prosecution for any future non-compliance of the regulation. This is known as ‘piercing of the corporate veil.’

The HPPA, under section 101(3), directors, officers, employees and agents, allows the crown to prosecute corporate directors, officers, managers, and all responsible employees and agents. The HPPA is amongst the few statutes in Ontario, which prevent such individuals from seeking protection against personal liability granted to them under the Ontario and the Canada Corporation’s acts. Convictions under this section also allow the crown to seize personal assets. The impending threat of such a prosecution is an effective deterrent, and in most cases, results in behaviour modification.

Enforcement agencies such as Toronto Public Health have laws like the City of Toronto Act, which enable them to further escalate progressive enforcement. A prohibition order can be issued against a rogue corporate owner with a record of multiple previous convictions. Such a court ordered prohibition prevents the corporation from committing future repeat violations. Penalties for the breach of a prohibition order are substantial and can range in the hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Probation orders, on the other hand, are imposed against individuals such as owners and operators for repeat non-compliance of regulations. These are a court-imposed order that prevents the individual from committing future violations. Consequences for breaching the conditions of a probation order are very serious and can lead to incarceration and/or substantial fines.

Conclusion

The primary purpose of public swimming pool and hot tub regulations is to protect those using these facilities. Although violations of these regulations are addressed, and public safety is not compromised, it would be beneficial to empower PHIs to use all the tools available.

As illustrated in the case study, if PHIs had the ability to issue offence notices (tickets) for minor swimming pool/hot tub infractions, it would significantly increase the number of enforcement actions for minor violations and decrease recurrence. For major, repeat offences PHIs can use progressive enforcement to deter non-compliant behaviour.

Increasing enforcement and compliance to the regulations not only allows public health units to optimally safeguard public health and safety, it also benefits public swimming pool and hot tub owners/operators by raising public confidence in their facilities.

Mahesh Patel, CIPHI(C), is a health hazard manager with Toronto Public Health. He holds a M.Sc. in water environmental management, a B.Sc. (honours) in applied chemistry, and a BAA in environmental health. As the safe water lead, he is responsible for both drinking and recreational water quality. This includes monitoring drinking water, beach water, and the compliance inspection program for public swimming pools, spas/hot tubs, and wading pools. As the legal and enforcement lead, Patel has played a major role in the development and implementation of policies and procedures. Internally he provides ongoing enforcement training and support to staff, while externally he continues to provide assistance and training to other Ontario health units and agencies for which he received an award of excellence from the Canadian Institute of Public Health Inspectors (CIPHI) in 2012. He can be reached via e-mail at mpatel@toronto.ca[21].

Mahesh Patel, CIPHI(C), is a health hazard manager with Toronto Public Health. He holds a M.Sc. in water environmental management, a B.Sc. (honours) in applied chemistry, and a BAA in environmental health. As the safe water lead, he is responsible for both drinking and recreational water quality. This includes monitoring drinking water, beach water, and the compliance inspection program for public swimming pools, spas/hot tubs, and wading pools. As the legal and enforcement lead, Patel has played a major role in the development and implementation of policies and procedures. Internally he provides ongoing enforcement training and support to staff, while externally he continues to provide assistance and training to other Ontario health units and agencies for which he received an award of excellence from the Canadian Institute of Public Health Inspectors (CIPHI) in 2012. He can be reached via e-mail at mpatel@toronto.ca[21].

- [Image]: http://poolspamarketing.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/bigstock-Auditor-AndD34F32.jpg

- Commencement of Proceeding By Information: http://www.e-laws.gov.on.ca/html/statutes/english/elaws_statutes_90p33_e.htm

- [Image]: http://www.poolspas.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/023_2_2.jpg

- http://www.health.alberta.ca/documents/Standards-Pools.pdf: http://www.health.alberta.ca/documents/Standards-Pools.pdf

- www.health.gov.bc.ca/protect/pdf/bc-pool-operations-guidelines.pdfManitoba: http://www.health.alberta.ca/documents/Standards-Pools.pdf

- http://web2.gov.mb.ca/laws/regs/pdf/p210-132.97.pdf: http://web2.gov.mb.ca/laws/regs/pdf/p210-132.97.pdf

- http://canlii.ca/en/nb/laws/regu/nb-reg-81-126/latest/nb-reg-81-126.html: http://canlii.ca/en/nb/laws/regu/nb-reg-81-126/latest/nb-reg-81-126.html

- http://assembly.nl.ca/Legislation/sr/regulations/rc961023.htm: http://assembly.nl.ca/Legislation/sr/regulations/rc961023.htm

- http://www.e-laws.gov.on.ca/html/regs/english/elaws_regs_900565_e.htm: http://www.e-laws.gov.on.ca/html/regs/english/elaws_regs_900565_e.htm

- http://www.e-laws.gov.on.ca/html/regs/english/elaws_regs_050428_e.htm: http://www.e-laws.gov.on.ca/html/regs/english/elaws_regs_050428_e.htm

- http://www.gov.pe.ca/law/regulations/pdf/P&30-1-10.pdf: http://www.gov.pe.ca/law/regulations/pdf/P&30-1-10.pdf

- http://www2.publicationsduquebec.gouv.qc.ca/dynamicSearch/telecharge.php?type=3&file=/Q_2/Q2R39_A.htm: http://www2.publicationsduquebec.gouv.qc.ca/dynamicSearch/telecharge.php?type=3&file=/Q_2/Q2R39_A.htm

- http://www.qp.gov.sk.ca/documents/English/Regulations/Regulations/P37-1R7.pdf: http://www.qp.gov.sk.ca/documents/English/Regulations/Regulations/P37-1R7.pdf

- http://www.justice.gov.nt.ca/PDF/REGS/PUBLIC%20HEALTH/Public%20Pool.pdf: http://www.justice.gov.nt.ca/PDF/REGS/PUBLIC%20HEALTH/Public%20Pool.pdf

- Commencement of Proceedings By Certificate of Offence : http://www.e-laws.gov.on.ca/html/statutes/english/elaws_statutes_90p33_e.htm

- HPPA section 13: http://www.e-laws.gov.on.ca/html/statutes/english/elaws_statutes_90h07_e.htm#BK16

- [Image]: http://www.poolspas.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/DSCN0851_2_2_1.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.poolspas.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/DSCN0950_2.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.poolspas.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/PSM_March_2014_HR-38.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.poolspas.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/DSCN0947_2_1.jpg

- mpatel@toronto.ca: mailto:mpatel@toronto.ca

Source URL: https://www.poolspamarketing.com/trade/ontarios-public-swimming-pool-and-hot-tub-legislation/