Preventing saltwater scale

By Bob Harper

Scale is one of the most common and serious challenges in saltwater pool maintenance. It typically forms first on the cell plates of the electrolytic chlorine generator (ECG), where it can remain undetected until the problem is well advanced. It also hampers the effectiveness and lifespan of the ECG cell, which can be costly both to pool owners, who may need to prematurely replace a cell, and to service companies, which will have to spend extra time on unplanned service calls to combat the issue.

As a natural byproduct of the electrolytic process that produces chlorine from salt molecules, scale will inevitably occur in every saltwater pool to some degree. However, it can be controlled—or, conversely, made worse—depending on the kind of salt and treatment products used in the pool and whether proper care and maintenance principles are followed.

The problem with scale

Scale is created when minerals precipitate out of solution and form mineral deposits. In saltwater pools, the most common minerals that create scale include calcium, phosphate, sulfate and silicate, all of which exist naturally in pool water and salt.

Pool water, in particular, contains high levels of calcium, which serves to protect pool finishes. When a pool is properly balanced, pH is approximately 7.2 to 7.8 and calcium is less than 400 parts per million (ppm), it generally remains dissolved in solution. As pH rises above 7.8 or the Langelier Saturation Index (LSI) exceeds +0.5, dissolved calcium is more likely to form insoluble compounds such as calcium carbonate, calcium sulfate, calcium phosphate and calcium silicate. These compounds collect on pool surfaces to comprise scale.

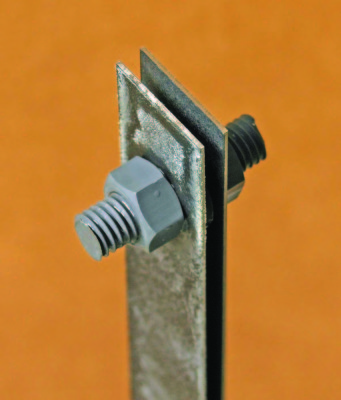

In the ECG, where salt molecules are converted to chlorine, the cathode plates produce a strong alkaline (high pH) substance called sodium hydroxide. Since the temperature on these plates is extremely high, as is the pH (almost 14), scale will naturally accumulate as the ECG operates.

As scale forms, it can cause significant heat buildup within the ECG. First, scale is a poor conductor of electricity, so a coating of scale on the cell plates makes the ECG work harder to push electric current through, generating more heat. Second, scale inhibits the natural cooling process within the ECG by reducing direct contact between pool water and the cell plates. As pool water passes through the plates, heat is transferred from the plates to the water; if scale is present, it prevents water from effectively cooling the plates. Excess heat causes damage to the plates’ protective coating, thereby shortening cell life.

Scale also reduces chlorine production, which, in turn, quickly results in chlorine demand, cloudy water and even algae growth. The ECG must also work harder to produce the required amount of chlorine.

The bottom line is that scale prevents the ECG from doing what it is designed to do— produce chlorine that maintains pool water quality. It can also shorten ECG cell life or result in failure, requiring premature replacement.