Understanding the effects natural disasters can have on pools

By Terry Arko

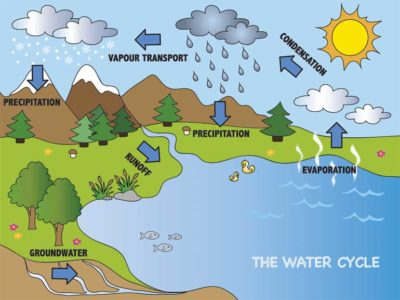

Water is an amazing, mysterious, and powerful element. To understand the capabilities of water and its effect on pools it is vital to understand how it travels throughout the world. The water cycle is a continuous loop of the various ways it transforms and renews itself.

Water can exist in three forms: vapour, solid, or liquid. For example, fog is a vaporous form of water as it rises into the atmosphere. As water transforms and travels it is subject to the environment in which it passes. Fog, for instance, rises up from the ground and passes through the surrounding air. During this process it picks up whatever is in its path (e.g. smoke, dust, or car exhaust). Snow can also pick up contaminants and bacteria and, as it melts into a liquid form, can be transported into nearby rivers and/or streams, or even end up in source water. In fact, in 1993, one of the largest outbreaks of Cryptosporidium in drinking water occurred in Milwaukee and was found to be the result of contaminated snow-melt feeding into Lake Michigan.

Water moves about this planet in many ways and, during this process, it is a great absorber and transporter of whatever it comes in contact with. Today, in this crazy climate, the challenges of source water contamination in pools can be many.

The evaporation problem

The average backyard pool in Canada contains approximately 68,137 to 75,708 L (18,000 to 20,000 gal) of water. An uncovered pool can lose roughly 6.35 mm (0.25 in.) of water per day—51 mm (2 in.) per week—due to evaporation. In a 68,137 L-pool, this is equal to losing 942.5 L (249 gal) per week and close to 45,425 L (12,000 gal) per year.

When water evaporates from a pool it changes from a liquid state into a gas or water vapour that travels back into the atmosphere. When water vapourizes, only pure water leaves the pool. As this happens, it also leaves behind more dissolved solids, which contribute to total dissolved solids (TDS).

There are two environmental factors which increase the acceleration of evaporation—temperature and humidity. For example, if a pot of water was placed on a table in a cool, humid environment, it could take weeks, even months, before it evaporated. However, if the pot was placed on the stove with the element on, it would evaporate in a matter of minutes. The more heat, the faster evaporation occurs.

Further, when heat is combined with dry air, water will vapourize more quickly. This is why evaporation is a big problem during times of drought when the air is warmer and drier.