Using a naturally occurring plant to clarify water

Studies reveal biofilm inhibiting properties

Laboratory studies revealed that extracts of Sphagnum moss significantly inhibit the growth of a number of planktonic bacteria including, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a common bacterium found in water and soil that can cause disease in animals and humans. These studies further indicated that the inhibitory effect was bacteriostatic (restricted the growth and activity of bacteria without killing them) and not bactericidal (destroyed bacteria). These results led to additional laboratory investigations of the effects of Sphagnum moss extracts on biofilm formation and removal. The following results and conclusions were presented at the ‘Biofilms IV conference in September 2010:

- Extracts of Sphagnum moss inhibit P. aeruginosa biofilms;

- The inhibition of biofilm formation and removal of established biofilm is time and dose dependent;

- Biochemical studies would indicate the inhibitory activity is probably due to a combination of multiple chemical compounds;

- Inhibition of biofilm by Sphagnum moss extracts may involve the modulations of virulence factors such as pyocyanin (C12H10N2O), which play a role in the control of the biofilm phenotype (an organism’s observable characteristics or traits); and

- The use of a natural, plant-based inhibitor of biofilm may be a useful alternative to current sanitizing methodologies.

Larger scale testing

In 2009, armed with this laboratory data and a working hypothesis that moss appeared to inhibit biofilm formation in small residential pools and spas, CWS pursued a public pilot test project with select partners in St. Paul, Minn.

Titled ‘The City of St. Paul Public Pools Green Initiative,’ the project was performed by CWS in partnership with the city’s parks and recreation department at the Highland Park Aquatics Center (HPAC) and U.S. Aquatics, a swimming pool service and maintenance company hired by the city as an unbiased technical consultant on the project.

HPAC’s public outdoor facility comprises four pools, which provided an ideal setting to quietly conduct the test project, as it provided two control pools that were treated with Sphagnum moss and two that were not. The project’s purpose was to determine if the pools’ chemical loads could be lowered to save money and create more natural water conditions, while still providing a safe, healthy swimming environment that met all standards required by the Minnesota Pool Code, Minnesota Rules (Parts 4717.0150 through 4717.3975). Before the natural system was installed, the test was cleared with the Minnesota State Health Department and the facility’s experienced team of certified pool operators (CPOs) were trained on its operation and told to treat the water in accordance with the state.

Simulating a moss bog

The Olympic-size 1,665,581-L (440,000-gal) main pool and 85,171-L (22,500-gal) children’s activity pool were set up as the Sphagnum moss test pools. All previous water treatment was left in place at the four pools.

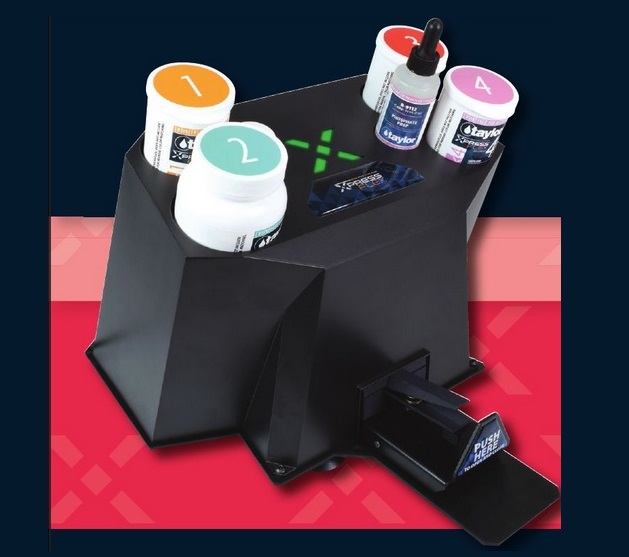

Specially processed Sphagnum moss was used in customized strainer bags, enclosed in crates and tethered within the lap pool’s underground surge tank. The smaller children’s activity pool relied on the Sphagnum moss treatment in an arrangement more similar to a residential pool system, with offline tanks housing the necessary Sphagnum moss dosage.

- Turbidity tests showed similar nephelometric turbidity unit (NTU) results similar to earlier tests performed on pool and spa water previously exposed to moss, with readings of 0.04 NTU.

- After strainers were 60 per cent clogged due to unusually high cottonseed dispersal, turbidity started to increase above 1.0 NTU. Although the increase was well below the accepted clarity level for pools (3 NTU), once the strainers were cleaned, turbidity levels returned below 0.05 NTU.

- Two weeks after the Sphagnum moss was introduced to the pools, a filtration pump automatically shut off due to back pressure in the system, which was also caused by the high levels of cottonseed. This went unnoticed overnight and the lack of filtration significantly clouded the pool. Once the system was operating again, the pool recovered within one day, without pool closure or use of additional chemicals.

- An immediate increase in free chlorine was also noticed. At one point, levels reached 8 parts per million (ppm) with no combined chlorine. Pool engineers were reluctant to decrease oxidation reduction potential (ORP), fearing the free chlorine would plummet. However, ORP was decreased by increments of 10 millivolts (mV) when free chlorine was greater than 4 ppm. As the season progressed, ORP settled at 650 mV and free chlorine levels were between 2-3 ppm, with no recorded combined chlorine.

- There was a gradual decrease in cyanuric acid (CYA, [CNOH]3) delivery by 10 ppm each week. By the end of July, cyanuric acid was no longer being added to the pool and levels gradually decreased to zero at the water’s surface and 10 ppm at the bottom.

- Concerned there would not be any free chlorine in the pool due to the decrease in cyanuric acid delivery, pool engineers were ready to add it manually if free chlorine levels decreased to 1 ppm. Throughout the remainder of the summer, however, free chlorine levels remained between 2-4 ppm without requiring cyanuric acid.

- Calcium hardness, pH and total alkalinity (TA) were also stable throughout the study period. Even with 1,000-plus bathers per day and extremely hot temperatures, the pH required very little adjustment beyond the controller.

- Calcium hardness levels remained at 500 ppm throughout the summer.